By Dr. Mary A. Papazian

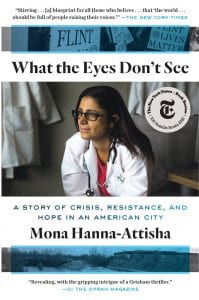

It was a real treat for me to join a recent Zoom webinar to discuss this semester’s campus reading program selection, What the Eyes Don’t See, by Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha.

Dr. Mona, as she is affectionately known, is a pediatrician, public health advocate and immigrant who practices in Flint, Michigan. Her book brilliantly shines a spotlight on the water crisis there, revealing how children were exposed to dangerous levels of lead.

Let me start by congratulating SJSU’s Kathleen McSharry, Daniel Rivers and others involved in our campus reading program for making this particular selection. What an incredibly timely book, especially given the events that have unfolded nationally since this past summer related to systemic racism and equitable treatment of all individuals.

You might ask what does the Flint water crisis have to do with systemic racism and equity issues? A lot, it turns out.

I began my academic career in southeastern Michigan where I taught literature at Oakland University, which is halfway between downtown Detroit and Flint. So I know the region well. My husband Dennis grew up in the Motor City in its heyday, when organized auto workers won power and, therefore, good salaries. Their labor enabled them to purchase cars and buy homes, while a shared commitment to prosperity allowed investments in the arts, education, and philanthropy. In the middle of the last century, Flint was, in many ways, the shining example of the American middle class.

But underneath the surface were inequities and racial disparities, issues that became clear and unmistakable when the auto industry fell on hard times in Detroit and Flint. The water crisis in Flint, as Dr. Mona’s book shows, exemplified an indifference to harm—in this case, lead poisoning—when it happens to People of Color and the less-advantaged. The crisis was a perfect storm of bad decision-making, powerlessness and systemic racism.

Much of the tragedy of Flint was a loss of belief in a shared humanity. Instead, some leaders acted as though the people of Flint did not deserve the attention and care other communities insist upon and take for granted.

What the Eyes Don’t See offers many lessons, far too many to list. But I will remember a hopeful perspective best summarized in Dr. Mona’s words:

Just as a child can learn to be resilient, so can a family, a neighborhood, a community, a city. And so can a country. A country can endure trauma and neglect and become a place where people are cared for, where democracy and equality and opportunity are once again encouraged and advanced. Where poverty is silenced instead of people. Where we nurture one another and create stable and safe environments for all children to grow up.

Talk about hitting the nail on the head! But we have a long way to go.

It is our shared humanity, I believe, that allows us to build the resilience of which she speaks, but we cannot do this on our own. Dr. Mona’s book makes clear that she did not work alone, and neither must we. The collective national outcries, marches and protests these past few months demand our attention, saying, in effect, “we believe in a shared humanity, and we see it in each other.” Together, we can see one another, and therefore nurture one another, no matter our social status, level of wealth or degree of privilege.

Two other fascinating angles appear as constant threads throughout the book: Dr. Mona’s own personal story and her deep love for children.

Her Iraqi background, family and sense of identity as a Chaldean with deep roots to antiquity deeply inform her story—Flint’s story—about children heart-wrenchingly harmed by indifference. Dr. Mona’s interactions with them, her joy in caring for them, and her ability to see each of these children as little ones with unlimited potential is stirring.

Second, What the Eyes Don’t See illuminates what can happen when science clashes with public policy and investigations into the truth are stymied by politics, prejudice and fear.

As a society, we have allowed extraordinary disparities to develop over years, and now inequities have been exacerbated nationally during the pandemic as they were locally by the water in Flint. Likewise, COVID-19 harms Black and Brown communities disproportionately. Our patchwork healthcare system reveals inequity. Law enforcement issues, the economy, access to quality education and housing—many inequities are being laid bare for some to notice for the first time, but for all to see.

This is what we mean when we use the term “systemic racism.”

The United States, long a beacon of hope, is renowned for government by the people. We want to believe that, but clearly it is not always the case. When our systems fail us, the people who demand recognition of our shared humanity raise their voices. We encourage our students to be active in civic affairs, because their voices matter.

As a society, we face a choice: let this break us apart in the way that Dr. Mona saw in Flint, or speak out together for the fairer, welcoming America in which we want to live.

I do not believe that any of us want democracy to be broken. That means each of us must get involved in our own way, according to our own values. We have seen this in action a great deal in recent months, both nationally, locally and on our campus. Our students are concerned and striving to make a difference. They have a powerful role to play in cultivating a better society for all of us.

I am very proud of our Campus Reading program and the culture of reading it fosters. First-year students share the experience of reading the same book, ideally giving them another way to orient themselves to college life—an opportunity to join the campus-wide community in discussion and reflection on vital, timely issues such as those reflected in What the Eyes Don’t See. I encourage everyone to read this important work.